Even if he causes pain, he will have compassion, thanks to the abundance of his faithful love, because he does not want to afflict or hurt anybody.” Wisdom 11:23 and 26 in the Apocrypha insists on God’s mercy, which is the counterpart of God’s omnipotence: “You have mercy upon all, because you can do everything you do not look at the sins of humans, in view of their repentance. Lamentations 3:22 and 31–33 lay some theological groundwork for a wider hope: “The faithful love of the LORD never ceases, his acts of mercy never end.

21 The global extent of God’s salvific plans is clear from such passages. Even the Egyptians and the Assyrians, the worst idolaters, will worship God, and God will bless them together with Israel (Isa 19:23–25). All nations of all tongues will come and see God’s glory (Isa 66:18) all peoples will see the salvation brought about by the Lord “all will come and worship me” (Isa 66:23). In Isaiah 49:6 God declares he wants his “salvation to reach the boundaries of the earth,” and in Isaiah 49:15, God uses a comparison: “Can a mother forget her baby and have no compassion on the little one she has given birth to? But even if she could, I shall not forget you.” Isaiah 51:4–5 announces the justification (i.e., making people righteous) and salvation given by God, so that the peoples “will hope in his arm,” God’s saving power. This justice is salvific, not retributive: it restores sight to the blind and liberates the prisoners from darkness and oppression. In the Old Testament, in Isaiah 42:1–4, the Servant of YHWH, whom Luke 3:18–21, followed by patristic authors, identifies with Christ, will bring justice to the nations.

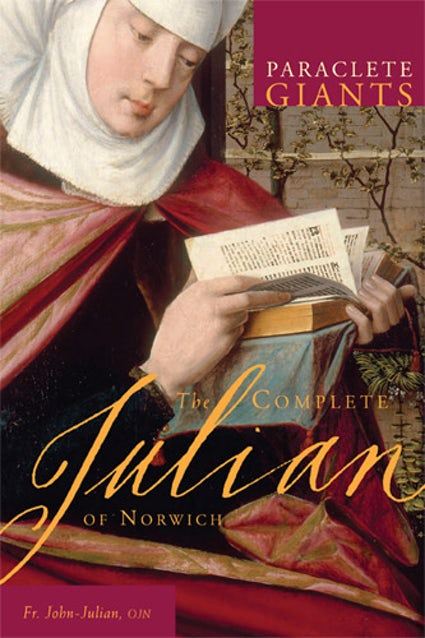

We are treated to explorations of Origenian universal salvation in a host of Christian disciples, including Athanasius, Didymus the Blind, the Cappadocian fathers, Evagrius, Maximus the Confessor, John Scotus Eriugena, and Julian of Norwich.

She outlines Origen's often-misunderstood theology in some detail and then follows the legacy of his Christian universalism through the centuries that followed. She argues that he was drawing on texts from Scripture and from various Christians who preceded him, theologians such as Bardaisan, Irenaeus, and Clement. Ramelli traces the Christian roots of Origen's teaching on apokatastasis. She demonstrates that, in fact, the idea of the final restoration of all creation (apokatastasis) was grounded upon the teachings of the Bible and the church's beliefs about Jesus' total triumph over sin, death, and evil through his incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension. She maintains that Christian theologians were the first people to proclaim that all will be saved and that their reasons for doing so were rooted in their faith in Christ. Ilaria Ramelli argues that this picture is completely mistaken. In the minds of some, universal salvation is a heretical idea that was imported into Christianity from pagan philosophies by Origen (c.185-253/4).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)